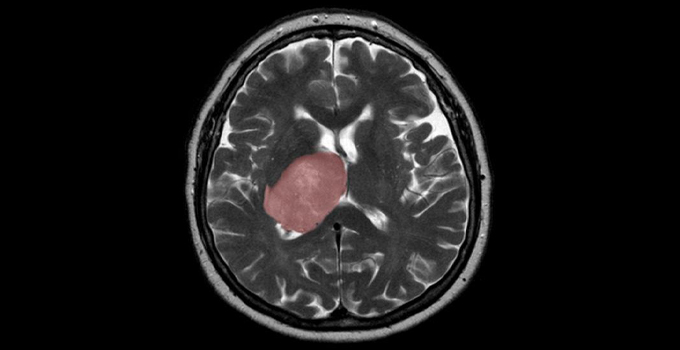

Researchers discover brain cancer may develop when tissue healing runs amok, uncovering new approaches to combat the deadly disease

The healing process that follows a brain injury, such as an infection or a stroke, could spur tumour growth when the new cells generated are derailed by mutations, Toronto scientists have found. This discovery could lead to new therapy for glioblastoma patients who currently have limited treatment options with an average lifespan of 15 months after diagnosis.

The findings, published today in Nature Cancer, were made by an interdisciplinary team of researchers from OICR, the University of Toronto’s Donnelly Centre for Cellular and Biomolecular Research, The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) and the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre who are also on the pan-Canadian Stand Up to Cancer (SU2C) Canada Dream Team that focuses on a common brain cancer known as glioblastoma.

“Our data suggest that the right mutational change in particular cells in the brain could be modified by injury to give rise to a tumour,” says Dr. Peter Dirks, senior author of the study, OICR-supported researcher, Dream Team co-leader, and Head of the Division of Neurosurgery and a Senior Scientist in the Developmental and Stem Cell Biology program at SickKids. “We’re excited about what this tells us about how cancer originates and grows and it opens up entirely new ideas about treatment by focusing on the injury and inflammation response.”

The research group, led in part by OICR and Princess Margaret’s Dr. Trevor Pugh, applied the latest single-cell RNA sequencing and machine learning technologies to map the molecular make-up of the glioblastoma stem cells (GSCs), which Dirks’ team previously showed are responsible for tumour initiation and recurrence after treatment.

Equipped with these single-cell analysis methods, the research group was able to accurately differentiate and study different types of tumour cells. Through analyzing 26 tumours and nearly 70,000 cells, they found new subpopulations of GSCs that bear the molecular hallmarks of inflammation.

This finding suggests that some glioblastomas may start to form when the normal tissue healing process is derailed by mutations, possibly even many years before patients become symptomatic, Dirks says. Once a mutant cell becomes engaged in wound healing, it cannot stop multiplying because the normal controls are broken and this spurs tumour growth, according to the study.

The study’s authors, including co-leading researcher, Dr. Gary Bader from the Donnelly Centre as well as graduate students including Owen Whitley and Laura Richards, are now working to develop tailored therapies target these different molecular subgroups.

“There’s a real opportunity here for precision medicine.” says Pugh, who is Director of Genomics at OICR and the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre. “To dissect patients’ tumours at the single cell level and design a drug cocktail that can take out more than one cancer stem cell subclone at the same time.”

In addition to funding from the Stand Up To Cancer Canada Cancer Stem Cell Dream Team: Targeting Brain Tumour Stem Cell Epigenetic and Molecular Networks, the research was also funded by Genome Canada, the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research, Terry Fox Research Institute, the Canadian Cancer Society and SickKids Foundation.