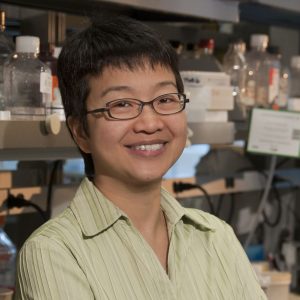

Dr. Jean Wang and colleagues developed a test that can help clinicians provide more personalized AML treatment.

A new gene signature test can improve early treatment decisions for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) by quickly assessing a patient’s risk of relapsing after treatment.

AML is a fast-growing blood cancer with a high rate of recurrence. Though most patients will go into remission after the standard treatment — a heavy dose of chemotherapy — a large proportion will see AML come back even more aggressively.

Relapses are common because AML is driven by leukemia stem cells, which chemotherapy typically doesn’t kill.

“Leukemia stem cells tend to survive chemotherapy, stay in the bone marrow and regrow the disease,” explains Dr. Jean Wang, Clinician Scientist at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre and Staff Hematologist at University Health Network who studies the biology of leukemia stem cells.

AML isn’t a single disease. Different patients respond to treatment differently, so it’s important to understand a patient’s risk profile to make the best decisions about their treatment.

Currently, risk is assessed by molecular and cytogenetic tests. But results for these tests can take weeks, and there’s often no time to wait because AML grows so quickly. As a result, most patients are treated with the same chemotherapy up front, and then are considered for additional treatments such as bone marrow transplant later on in the disease course, depending on their risk assessment.

But now, Dr. Wang and her colleagues have developed a laboratory test that can assess an AML patient’s risk of relapse and deliver results within 24 to 48 hours of diagnosis. In a study partially funded by OICR, they identified a signature of 17 genes (called the “LSC17 score”) that captures the “stemness” properties of a patient’s AML cells at diagnosis, and provides a rapid prediction of how well the patient will respond to standard chemotherapy. The new test uses the Nanostring platform to measure the expression level of the LSC17 genes and calculate a score. The higher the LSC17 score, the higher the risk of AML relapse after standard treatment.

Dr. Wang says this new test can help clinicians put patients on a more personalized treatment plan. If a patient has a high LSC17 score, meaning they have a high risk of relapse after standard chemotherapy, they could be considered for stronger up-front therapy or a clinical trial of an experimental therapy. This could ultimately improve their chances of survival without them having to go through standard chemotherapy when it’s not likely to cure them.

“With this test, clinicians can get information about whether their patient is high-risk or low-risk within just a day or two,” Dr. Wang says. “Having all the information available will help clinicians make better treatment decisions for their patients.”

The LSC17 test could also strengthen research into new treatments for AML by showing whether experimental therapies will help patients who aren’t likely to respond to standard chemotherapy. “Using it is a correlative test in clinical trials would be really valuable to identify drugs that can benefit high-risk patients,” Dr. Wang says. “One big problem in AML right now is that there are not a lot of good treatment options for high-risk patients.”

The test has been developed and validated in the CLIA-certified Advanced Molecular Diagnostics Lab at Princess Margaret, and the protocol is easily established and reproducible in other lab locations. Now, Dr. Wang says the next step is to make it accessible to clinicians. Though it is currently available through Princess Margaret, she says it needs to be more widely available to benefit patients and to determine how it can best integrated into clinical practice.

“We’ve received a lot of clinical interest,” Dr. Wang says. “Now we need to make it available to both clinicians and researchers and get them using it, and we can take it from there.”

***

This work was supported by OICR and several other organizations across Canada. A full list of funders is available in the ‘acknowledgements’ section of this journal article.