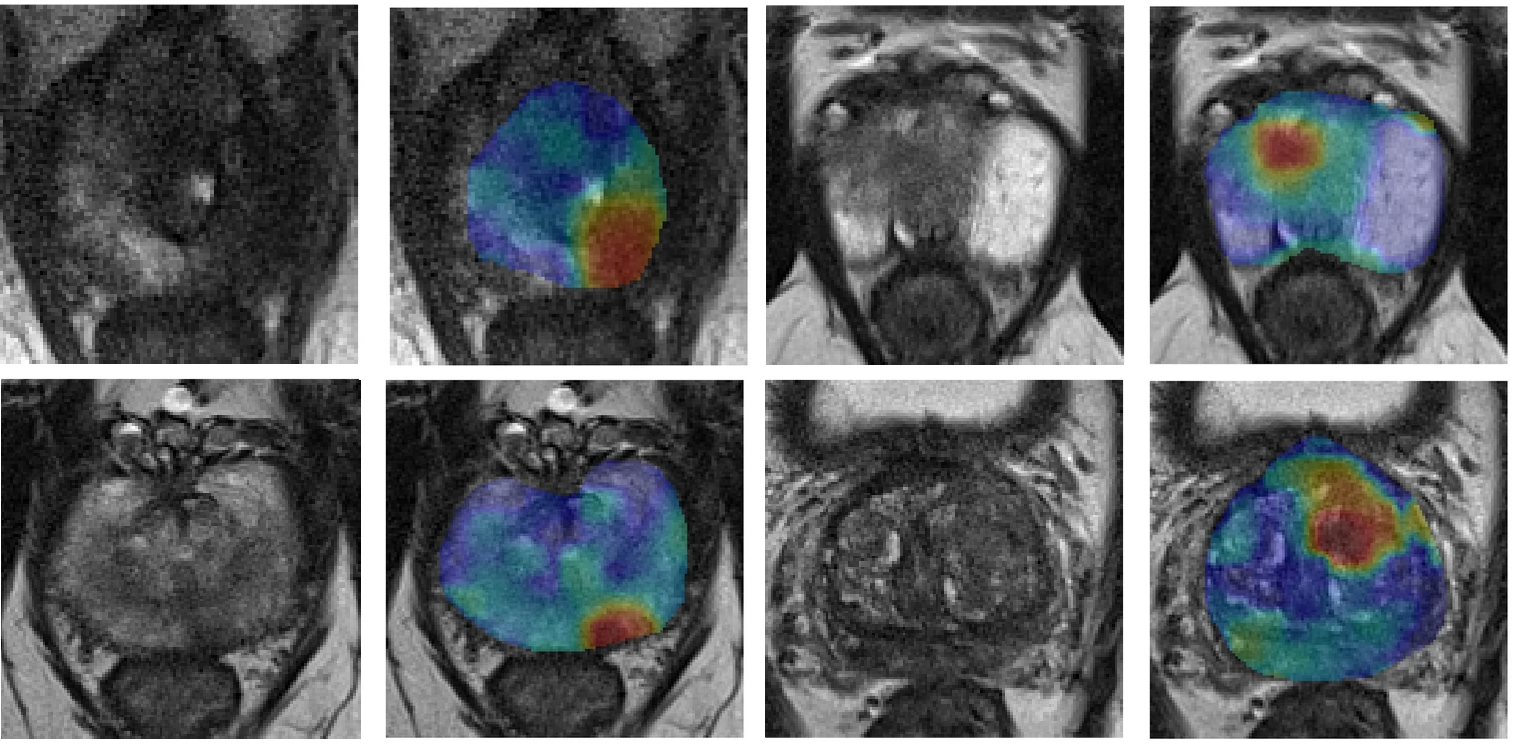

Synthetic correlated diffusion imaging detects tumours and their margins by capturing the movement of water through tissue.

Cancer can be tough to distinguish from the healthy tissue around it, especially in the black-and-white image from a standard MRI.

But new MRI technology is harnessing one of cancer’s unique properties — its irregular density — to ‘light up’ cancerous tissue and pinpoint where it is located.

Synthetic correlated diffusion imaging uses MRI signals and a sophisticated algorithm to capture how water molecules move through tissue at different levels. Cancer cells are packed less uniformly than other tissues, and so the irregular movement of water indicates the presence of cancer.

The system generates an image that resembles a heat map — the more intense the irregular movement of water in one area, the brighter it appears. Cancerous tissue shows up as bright red spots, which researcher Dr. Alexander Wong says makes it easier to see tumours among the surrounding tissue.

“By having the tumour light up in red, we can better localize and detect it, and also get a clearer picture of the margins around it,” says Dr. Wong, an OICR Affiliate and Canada Research Chair in Artificial Intelligence and Medical Imaging at the University of Waterloo.

Dr. Wong and his colleagues spent six years developing synthetic correlated diffusion imaging, hoping to create a cancer-targeted alternative to the standard MRI, which produces images where cancer can be difficult to see.

In addition to Dr. Wong, Dr. Masoom Haider, Professor of Radiology at the University of Toronto and an OICR Clinician Scientist, and University of Waterloo graduate students Hayden Gunraj and Vignesh Sivan, were the core members of the research team. They collaborated with experts at OICR and multiple Toronto hospitals.

Their preliminary study was published in Scientific Reports and describes how synthetic correlated diffusion imaging accurately detected tumours and their margins in 200 patients with prostate cancer. They are also conducting another study testing their new MRI system with breast cancer patients, and Dr. Wong says results are similarly promising.

These studies show that synthetic correlated diffusion imaging has the potential to strengthen early detection, which is crucial to surviving both prostate cancer and breast cancer. It could also help track tumour growth and inform more precise surgeries and therapies.

“I can see a lot of different areas where this could be really important,” Dr. Wong says. “It could help a lot of people get earlier treatment as well as more personalized, targeted treatment.”

Encouraged by the positive results, Dr. Wong says the research team hopes to do a much larger study to refine and validate their technology. They are also exploring how to best integrate synthetic correlated diffusion imaging into clinical practice.

Because it uses the same technology as standard MRI, but with different pulse sequences and specialized software to process data, integration could be relatively seamless.

“That’s the beauty — the physical piece of hardware doesn’t change,” says Dr. Wong. “We designed it so that it can easily fit within the imaging workflow.”

He says it’s also important that results are delivered in a way that resonates with clinicians and helps them make informed care decisions.

“At the end of the day, this is a tool,” Dr. Wong says. “It needs to be something that clinicians can effectively leverage in order to have an impact on what matters most: the health and wellness of patients.”