As a radiation oncologist at the London Health Sciences Centre, Dr. David Palma is on the front lines of treating cancer patients with radiotherapy. Despite huge advances in radiation technology over the past few decades, Palma and his colleagues have noticed that clinical trials proving the benefits of these new technologies are not keeping pace – meaning these advances are not always reaching patients. To overcome these challenges and advance treatment, Palma formed the Canadian Pulmonary Radiotherapy Investigators Group (CAPRI) to support radiotherapy clinical trials and get them up and running as quickly as possible.

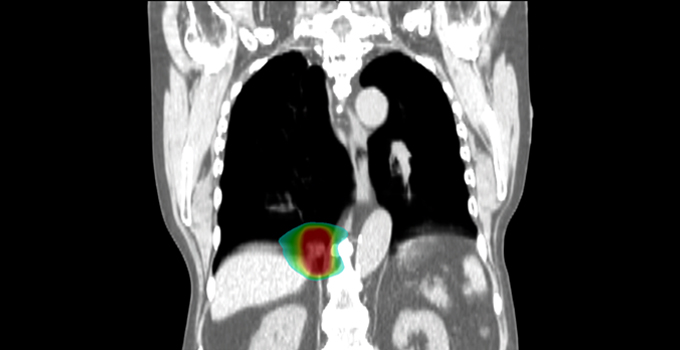

“In lung cancer, we used to treat patients with beams of radiation from both their front and their back, shooting right through the body, which is the way it had been done for almost 60 years,” says Palma, who is also an OICR Clinician-Scientist. “Now we can target tumours extremely precisely, and we can even see tumours move as a patient breathes and turn the radiation beam on when the tumour gets to the right spot. This allows us to reduce the radiation given to normal tissue and deliver higher doses to tumours.”

Palma notes that with new radiation innovations, there is often not the same high level of supporting evidence as there would be for a new medicine, namely a randomized trial to prove a benefit. This can lead to controversy. “One of the best examples of this is proton therapy, a type of radiation that might be better at sparing normal tissue, but is more expensive. It has been introduced in many countries, but without randomized trials. This has led to decades of debate: are protons really better, and if they are, is the improvement worth the cost? Only now, decades after proton therapy was introduced, are large randomized trials underway. If trials are not done, then some people are believers, some are not, and no one really knows what the best treatment is.”

Palma explains that the reason it is so hard to get radiotherapy trials up and running is because it is often that a technology or ‘therapy design’ is being evaluated and not a new product. Unlike with new drugs or medical devices, researchers looking to run radiotherapy trials cannot rely on the funding of producers to conduct clinical trials. “Another factor is that these trials can take a lot of time. You are normally looking at two to three years from coming up with an idea to just having the first patient enrolled in a trial. By the time to you complete the trial and analyze the results, it is often more than a decade. And by then, the technologies have changed again”.

Three years ago, Palma set out to change this paradigm by forming CAPRI to speed up the development and initiation of clinical trials and provide the necessary funding. Through a philanthropic donation, and operating funds from OICR, CAPRI is able to provide financial resources for up to five trials at a time. To accelerate the time from conception to trial launch, CAPRI uses a streamlined application process and strictly requires the trials to launch within a few months of approval. CAPRI also encourages smaller cancer centres to get involved in radiotherapy clinical trials by recognizing them as authors on published clinical trial results – a type of recognition that these centres do not often receive.

CAPRI supports two different types of clinical trials – those aimed at improving the quality of life for patients and others focused on increasing cure rates. Clinical trials in CAPRI’s current portfolio are aiming to recruit 287 patients in total – so far approximately 130 patients have enrolled. Palma holds out a CAPRI trial called PROACTIVE as an example of how these trials can improve quality of life for patients. The trial is assessing a new way of delivering radiotherapy to palliative lung cancer patients that will limit the amount of radiation delivered to esophagus.

“Twenty to 30 per cent of patients get what can be thought of as a sunburn on their esophagus. This means that they spend some of their limited remaining time in pain and have difficulty swallowing as a result, leading to weight loss,” explains Palma. “The trial is really the only way that we can see if we can actually reduce this burden on patients and we are hopeful that the results will show a path to improvement.” PROACTIVE is expected to complete its full accrual of 90 patients within the next few weeks.

Although it is not a CAPRI trial, Palma points to some of his recent research to show how clinical trials are key to improving cure rates for cancer using radiation. The trial, called SABR-COMET, challenged the assumption that metastatic cancer is incurable by treating patients with one to three spots of cancer that has spread using a method of precisely focused therapy called stereotactic radiation. The Phase II randomized trial, which was carried out in Canada, Australia, Scotland and The Netherlands, found that treating patients with metastatic cancer with this method improved median survival by 13 months. A follow-up study called COMET-10 will now evaluate the effectiveness of the strategy on patients with four to 10 spots of cancer that has spread from its primary site.

“What trials like PROACTIVE and COMET show is that radiotherapy clinical trials are central to improving both cure rates and the quality of life for patients. That is why initiatives such as CAPRI are so important,” says Palma. “We believe by supporting and accelerating these trials we are putting Canadian researchers in a position to advance patient care.”