A global collaboration highlights the need for personalized approaches for treating various conditions involving fluctuating hormone levels.

An international study published in The Lancet Oncology is the largest and most comprehensive to highlight the links between hormone therapy and the risk of breast cancer in women under the age of 55.

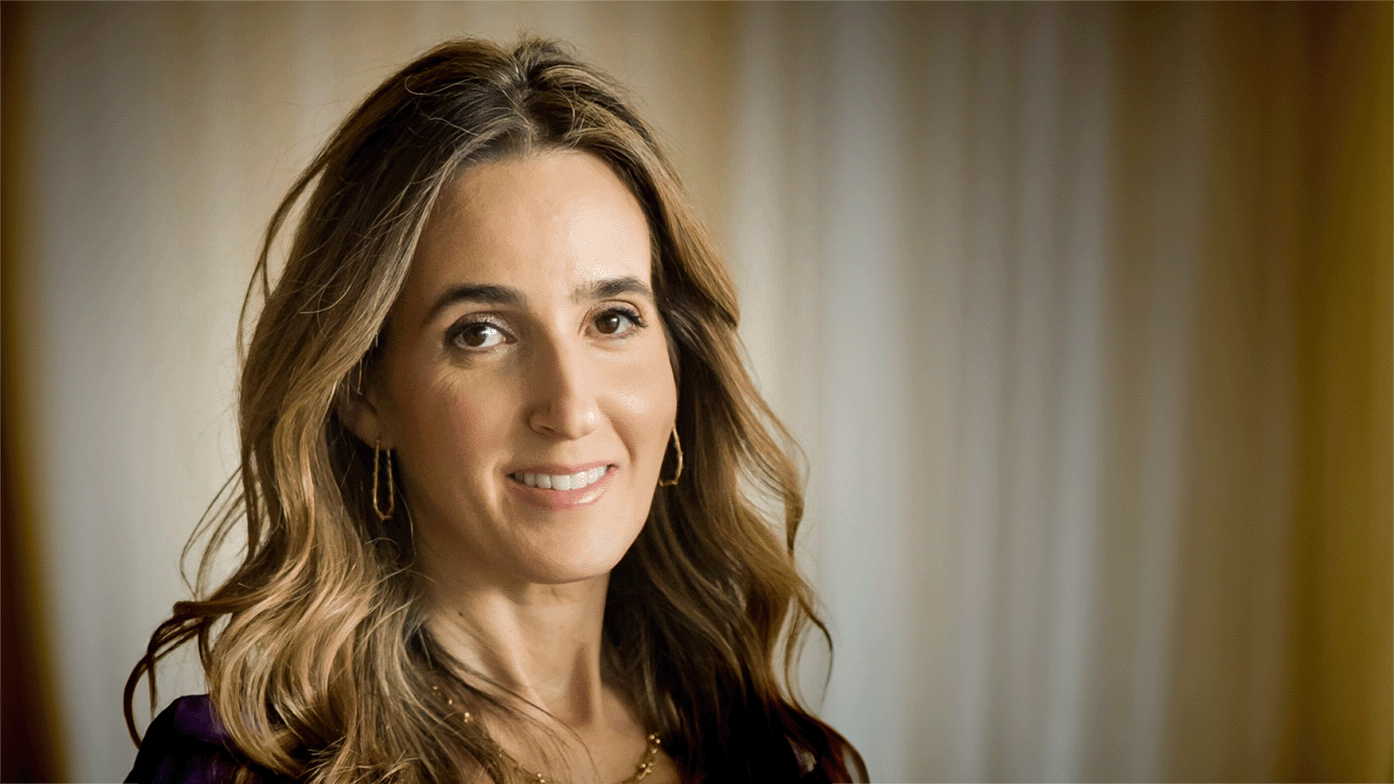

Researchers pulled together data from 13 cohort studies across North America, Europe, Asia and Australia — including The Canadian Study of Diet, Lifestyle and Health, co-led by OICR’s Dr. Victoria Kirsh — as part of a large collaboration known as the Premenopausal Breast Cancer Collaborative Group. They found one type of hormone therapy increased women’s risk of early-onset breast cancer, while another may reduce their risk.

Hormone therapy is prescribed to manage symptoms related to menopause or following gynecological surgeries like the removal of the uterus (hysterectomy) or the ovaries (oophorectomy), as well as other conditions affecting hormones levels.

Previous research had found links between hormone therapy and breast cancer risk in women above 55 — who more likely to be taking hormone therapy. But premenopausal women also face symptoms caused by fluctuating hormone levels.

“Symptoms necessitating hormone therapy aren’t confined to post-menopausal women,” says Kirsh, who is Interim Director of the OICR-hosted Ontario Health Study. “They can happen to peri-menopausal and younger women, who may then consider hormone therapy, so it’s important they understand the risks involved.”

Between the 13 cohorts, the study analyzed data from 459,476 women ages 16 to 54, about 15 per cent of whom reported having used hormone therapy.

They found dramatically different risks of breast cancers depending on the type of hormone therapy taken. Women who took a combination of estrogen and progesterone saw their risk of young-onset breast cancer jump by 18 per cent, while women who took estrogen alone saw their risk of young-onset breast cancer reduced by 14 per cent.

The risk of young-onset breast cancer among women taking estrogen and progesterone was particularly high for triple-negative disease compare to other subtypes.

Kirsh says the results largely mirror the risks for women over 55.

“The takeaway here is that we need personalized approaches to menopausal symptom management,” Kirsh says. “When women consider taking hormones, particularly combinations of estrogen and progesterone (which is necessary for women with an intact uterus to counteract the increased risk of endometrial cancer associated with estrogen-only therapy), they need to weigh the benefits of symptom relief against the associated risks of breast cancer.”