New research shows that prostate cancer and Ewing sarcoma exploit a biological process to their advantage.

An international study co-led by OICR researchers has demonstrated how two forms of cancer work to suppress the immune system and could inform new ways to diagnose and treat the diseases.

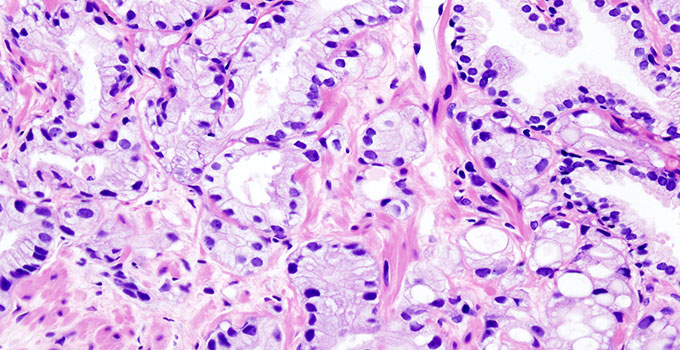

In their study, published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, researchers from Ontario, British Colombia and Europe looked at prostate cancer and Ewing sarcoma – a rare cancer of the bones and soft tissue that affects children most often – and identified a novel mechanism that contributes to the growth of both types of cancer and help them cause abnormalities in a patient’s immune system.

The team found that Ewing sarcoma and prostate cancer cells release ‘extracellular vesicles’ that can cause inflammation and DNA damage in the non-cancerous cells surrounding a tumour and ultimately lead to the suppression of a patient’s immune system.

These extracellular vesicles can also be taken up across the body by immune system cells, causing them to release ‘pro-inflammatory cytokines’ that help drive tumour growth and suppress immune responses that can help fight cancer.

“Our findings reveal a new biological pathway by which tumour cells are able to dampen and evade the body’s immune system,” says Dr. Lincoln Stein, Head of Adaptive Oncology at OICR and one of the paper’s senior authors. “This raises the possibility of developing diagnostic tests based on these insights to determine which patients are likely to benefit from immunotherapy. In the future, we may also be able to develop drugs that reverse the immune-evasion pathway identified in this study.”

The team went on to examine how exactly these extracellular vesicles work to drive tumours and suppress the immune system. They found a novel mechanism involving the expression of ‘non-coding DNA’, which makes up the bulk of our genome but is only now being linked with cancer. This part of the genome has been known as the ‘dark genome’.

One of the key findings was that the DNA and RNA sequences from the non-coding elements of Ewing sarcoma and some prostate cancer cells mimic sequences expressed by viruses and other pathogens. In fact, they ‘infect’ normal cells by tricking them into thinking they are being infected by a virus, generating a persistent inflammatory response that supresses rather than actives the immune system.

They also found that the uptake of these extracellular vesicles in normal immune cells in the blood can leave a “footprint” in cells that can be identified and measured as a novel approach to detect cancer. They hope this discovery could lead to new tools to detect, monitor and treat the disease.

“This study shows the power of collaborative science, allowing us to uncover a really complex process showing how tumour cells exploit ancient biology to their advantage, which we can then hopefully use for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes,” says Dr. Poul Sorensen, a distinguished scientist at the BC Cancer Research Institute and Professor of Pathology at the University of British Columbia and another of the study’s senior authors.

The research was also co-led by Dr. Laszlo Radvanyi (co-senior author), President and Scientific Director of OICR, whose team included Dr. Peter Ruzanov and Dr. Valentina Evdokimova as lead authors.

This story was adapted in part from an article by BC Cancer.