Dr. Glenn Bauman recently completed his time acting as an advisor within OICR’s Clinical Translation program. In this Q and A he chats about his longtime involvement with OICR, the Institute’s critical support of his practice-changing prostate cancer research and what’s new in cancer research in London, Ontario.

Bauman is Vice Dean, Clinical Academic Affairs at the Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry at Western University an Associate Scientist at the London Health Sciences Centre Research Institute and is the Director of the Centre for Translational Cancer Research.

What is your current clinical and research focus?

I’m a radiation oncologist, and my primary area of practice is genitourinary cancer, particularly prostate cancer. Until recently, I also treated patients with brain tumours, and I continue to care for children with cancer, mainly those with solid tumours. From a research perspective, much of my work has focused on high-precision targeted radiation—technologies that allow radiation to be delivered very accurately. Over the past 10 to 15 years, my focus has increasingly shifted toward imaging, because while we have sophisticated tools to deliver radiation, their effectiveness depends on knowing exactly where to aim. Advanced imaging is critical for that.

How did you become focused on imaging?

Around 2008, we received a large CIHR team grant to study multimodality imaging for prostate cancer. The goal was to localize cancer within the prostate gland itself, which could help us understand how aggressive a patient’s disease was. That information could then be used to better target procedures, whether biopsies, radiation, or surgery.

What was unique about the imaging platform your team developed?

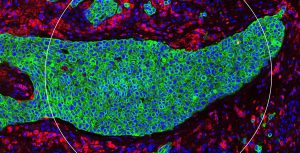

The team grant allowed us to build a platform that combined imaging done before surgery with digitized pathology afterward. This meant we could directly correlate imaging findings with the actual distribution and grade of cancer in the prostate. It gave us a reference standard to evaluate which imaging approaches were most predictive and how they could be used most effectively. We started with standard clinical tools like ultrasound and MRI, but the platform was designed to incorporate new imaging techniques as they emerged.

How did OICR become part of this work?

As new imaging modalities became available, we began to look closely at PSMA PET scanning. This is where the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research (OICR) entered the picture. At the time, OICR was running its Smarter Imaging Program, which focused on developing new imaging approaches for prostate cancer. Because we already had the infrastructure in place, we could take projects from Smarter Imaging and validate them efficiently, assessing feasibility and clinical value. We evaluated several approaches, including sodium MRI, hyperpolarized carbon MRI and PSMA PET clearly emerged as the most promising.

How did PSMA PET move from research into routine clinical care?

One of the advantages of PSMA PET is it provides whole body imaging for prostate cancer and its usefulness for evaluating men with suspected recurrence was emerging from studies in other jurisdictions like Germany and Australia. We advanced PSMA imaging into a prospective study (PICS) focused on biochemical recurrence after radiation therapy for prostate cancer. As awareness of usefulness of PSMA PET grew, I was invited to help lead a prospective registry through Ontario Health. That enabled PSMA PET imaging to be scaled across the province and deployed to thousands of patients.

As this new PSMA PET imaging has been approved by Health Canada and Ontario Health, it is now used as a standard of care test routinely for men with prostate cancer. What’s unique is that this technology was developed through OICR, advanced through the research pipeline, and then successfully transitioned into the healthcare system. That it’s now a standard-of-care test available outside of research studies is very satisfying to me and something I look at as a capstone of my career.

How have you seen OICR evolve over the years?

My connection with OICR actually began when I received my first major research grant from its predecessor organization, the Ontario Cancer Research Network (OCRN). OCRN was great for cancer research in the province because it provided a lot of different opportunities for researchers to get involved. OICR in its early days had to focus on building its institutional footprint and programs, but now that it is a mature and established organization I think we are seeing it carry out its role of leading and enabling cancer research across the province with increased vigour. There is a very focused effort to engage with partners across Ontario, and I think that will continue to pay dividends.

Can you tell us about your work in the Clinical Translation Program?

Translation depends on strong clinical linkages, which can be challenging for research institutes such as OICR that are not embedded in a hospital. To address this, OICR recruited medical leaders who straddle both clinical care and research. In this role I saw myself as providing a clinical reality check—advising on feasibility, engaging clinicians, and offering feedback on projects. I also had a foot in camps that might not normally be represented in traditional cancer drug trials – imaging and radiation therapy.

I was also happy to be involved with Clinical Translation (CT) initiatives such as the Window of Opportunity clinical trials network, which have broadened collaboration and made opportunities for translation more accessible. Another positive development was CT’s shift towards biomarker-focused research, which aligns well with the strength of OICR’s core research programs in these areas. It has also been great to see OICR increase their focus on biomarkers for imaging, precision radiation, and precision surgery, not just genomics or drugs.

What’s happening in cancer research in London, Ontario?

In London, we are fortunate to have a growing critical mass of cancer researchers spread out across the research institutes of our two major hospitals here and at Western University. However, we recognized the need for connection across institutional boundaries, which led to the creation of the Centre for Translational Cancer Research, a network that brings the community together through events, workshops and lectures.

The cancer research community in London is well known for our strength in imaging, but we are also doing exciting things in other areas such as Dr. Saman Maleki’s work on the microbiome as a modulator of cancer therapy, and the theranostics research and clinical care of Dr. Ting Lee, Dr. David Laidley and Dr. Lilian Hannah and others focused on imaging and treatment with radiopharmaceuticals integrated with other therapies. Another important part of our infrastructure is the Verspeeten Genome Centre led by Dr. Beckham Sudakovic, which is enabling cutting-edge, genomics-based research and care.

Great things are happening here, and I am excited to see what’s next as we continue to contribute to cancer research in Ontario and worldwide.